Those of you who’ve been reading this blog for longer than is psychologically healthy may remember I trekked to the top of Mount Ararat a couple of years ago.

Those of you who’ve been reading this blog for longer than is psychologically healthy may remember I trekked to the top of Mount Ararat a couple of years ago.

At this time, I wrote an article on the trek for an outdoorsy magazine, though unfortunately they decided against using it; embarrassingly, this was said to be because the accompanying photos weren’t good enough, but on the other hand it wasn’t any kind of slight on my writing.

Anyway, so that the words won’t go to waste – and also because it’s a sunny Sunday afternoon and the balcony beckons – I thought I’d share this tale of travel and trekking with you, my loves. So, complete with the punning title that may have been the real reason it was bounced, here it is…

Ararat’s The Way To Do It

The eight of us caught a plane in Istanbul, and a couple of hours later, landed in the town of Van.

Appropriately enough, we then boarded a van, and after travelling for an hour or so (on roads of varying quality), chatting as we went, Mount Ararat loomed into view.

There were patches of ice and snow on its sides, and the first time we saw it, the top was obscured by cloud.

The van stopped, we stared up at Ararat, and a few minutes later we were en route again, continuing our journey towards the town of Dogubeyazit.

I think it’s fair to say conversation was slightly subdued, as we all mulled over the prospect of the as-yet-unseen summit.

According to the bible (specifically Genesis 8:4), after the flood, Noah’s ark landed on Mount Ararat.

The mountain we today know as Ararat is in Turkey, where it borders Armenia. Until just over five years ago, for security reasons, the Turkish authorities refused access to climb the mountain. Today, you can climb Ararat if you have the appropriate permit and guide. And if your legs and lungs are up to it, of course. It may not be an accident that the mountain is known locally as Ağri Daği, or ‘the mountain of pain’.

We checked into our hotel in Dogubeyazit, and had a meal on the roof terrace, which gave us a view of Ararat.

The clouds had cleared from the top, enabling us to see the summit, which was surprisingly flat-looking, like a boiled egg with its top removed, or a de-walnutted Walnut Whip. We looked at it, and talked about the Ark, and the claims that parts of it had been found on the mountain.

The next morning, we set off from the hotel, stopping en route to collect our permits.

After a minibus trip to the small village of Eli (2200m), we continued on foot, but not before being introduced to a man who – rather surprisingly – claimed to be the owner of Ararat. He said this with a smile, so I guess he didn’t want us to take his claim too seriously. Shame, really, as I’d been practising my scissors-paper-stone technique over the previous weeks, and was wondering if he might be willing to gamble. Ah well.

Backpacks on, we trekked for about five hours, and here, at the base of Ararat itself, the veins of ice and snow which we’d seen the previous day came into human scale, looking a lot larger and more daunting than they had from a distance. But I’d have to say that was true for the rest of the mountain as well.

We arrived at Green Camp (3200m), where we’d be spending the night. It lived up to its name, with tents pitched all around on soft grass, and horses and the odd goat grazing nearby. During the night, the horses whinnied occasionally, and sometimes I heard them running around a bit. Just harmless horseplay, I thought, and turned over in my sleeping bag, hoping bad puns weren’t a symptom of altitude sickness.

Altitude sickness is, of course, something to be avoided at all costs – particularly if you’re in a group, as one sick person could start to jeopardise the others – so we spent the next day acclimatising.

Not that this meant we took it easy, mind you, and we walked up the increasingly rocky terrain to just under 4000m, where we could see High Camp (insert your own Graham Norton joke here), which would be our next port of call.

We made our way back down to Green Camp, and as the rockiness gave way to grass once again, I decided that the after-hours gambolling of the horses was a small price to pay for the springiness underfoot.

A quick health check of our group proved encouraging – nobody seemed to be having trouble breathing, though there were one or two uncertain stomachs. Generally, we seemed in good shape, which was reassuring.

So, the next day, we trekked back up the previous day’s route, and on to High Camp.

The grass and flowers gradually disappeared until I realised we were walking on a mixture of rocks and gravel, which made it harder going. The tents at High Camp had actually been pitched amongst the rocks, and when we gathered for our evening meal, it meant hopping from one rock to another to get to the kitchen tent – a bit of an effort, and an unwelcome one when we really needed to be saving our energy for the next day, when we’d head for the summit.

Starting at 3am. I think I speak for the group when I say, on the subject of that start time: urgh.

Mindful of the pre-dawn start, we turned in early.

For fun, the wind decided to make getting to sleep into something of a challenge, rattling the sides of the tent just often and loudly enough to wake you, and of course once you’re awake and realise you really need to get back to sleep as soon as possible, that’s pretty much the last thing you can do.

As it inevitably would, though, 3am came, and by the light of a full moon and our head torches, we groggily ate some soup and pasta before setting off.

There’s something unreal about trekking at such an hour; the brain’s foggy from lack of sleep, the near-dark makes it all feel vaguely dreamlike, and the body’s not so keen to be up and exerting at such an hour. Your visual input is (initially, at least) limited to the light cast by your head torch, and all you can hear around you is ragged breathing and the crunch of feet on scree, and … well, I’d say it’s no surprise that it all feels a bit less than real.

Which could be seen as a hint of altitude sickness, but I’d argue it was just fatigue.

The gravel and rocks underfoot became mixed with ice – we were attempting the summit before dawn so the scree and water would be frozen and easier to walk on – but as we continued our plodding progress upwards, the rocks and gravel became less present, snow took over, and we stopped and strapped on our crampons.

The sun was rising behind Ararat, casting a shadow over Dogubeyazit, and we shed our head torches. As we continued, the sunlight twinkled on the snow all around us, as if a glitter lorry had shed its load.

The summit was close by now, my tentmate said, though when I looked upwards I had a notion it was lurking over the brow of the highest visible point. When you think you’re almost done, there’s all too often a bit further to go: this is as true on mountains as it is in life generally, and so we steadily traversed the snow in the area known as ‘the saddle’, because of its shape, heading for the pommel. Er, I mean summit.

The wind was starting to bite, and my leg muscles were complaining, but up ahead, I could see some other members of the group waving, so I knew the summit must be close.

I’ll freely admit I felt quite emotional as I wearily took the last few steps – my eyes misted over as I thought about the members of the group who had come to Ararat for religious or cultural reasons – and there was a round of congratulatory hugs and handshakes as we stood there, at the top of Mount Ararat, 5137m above sea level.

There was no shelter from the wind on the summit, and it jostled coldly, so we lingered just long enough to check out the view from all angles (Little Ararat does seem to live up – or down –to its name when viewed from the summit of its larger sibling), to take some photos (though that meant removing gloves, which was less than fun), and then we started to descend.

It’s said that the majority of accidents and injuries occur when descending, and it’s easy to see why; the adrenaline rush lingers even as the fatigue starts to kick in, inviting carelessness, and there’s the unbreakable law of gravity as well, so we were careful and slow to descend, especially as the ice underfoot was starting to thaw out in the sun.

We made it back to High Camp just after noon, and stayed there long enough to have some tea and chocolate and a hint of a breather before going on down to Green Camp. Arriving there mid-afternoon, it was a relief just to stop moving, and I realised we’d been on the go for about twelve hours.

It won’t come as a surprise if I tell you we all turned in early that night, and slept well.

The next morning, we walked down to Eli, at a relaxed pace, and we were met by the minibus, which took us back to Dogubeyazit.

If we wanted, our guide said, we could see the Ark the next morning. Of course we said yes, though I must admit I was a little disappointed that it seemed so easy – the Ark, it appeared, was neither lost nor in danger of any raiders. Or was that another Ark I was thinking of?

When in Rome and all that, so a group of us used the free afternoon to visit a Hamam, or Turkish Bath, in Dogubeyazit. We spent a couple of hours jumping in and out of water which was alternately boiling and freezing, and for a small extra fee I received an expert pounding at the hands of the masseur.

I stepped out onto the streets of Dogubeyazit feeling cleaner than I had in days. A local child approached me, carrying a set of bathroom scales, and offered to weigh me for one lire. Never mind any health-related effects of the trek, I had the sneaking suspicion that in the last few hours I’d shed a few pounds in grime alone.

The next morning, after a brief detour to see a ‘meteor crater’ which looked suspiciously like a large hole in the ground, we arrived at the Noah’s Ark National Park Visitors’ Centre. No ifs, buts or maybes, this place was confident it was the real deal.

The Visitors’ Centre was just that – a room with displays and newspaper clippings about the location, manned by a friendly chap called Hassan who’s known as the ‘Guardian of the Ark’. Outside the building, a path led through some trees to a vantage point overlooking a valley, where we could look at the Ark.

Or, at least, the fossilised remains of the Ark – which rather resembled a stretched oval-shape in the earth. They say it’s made of stone, though from the viewing point it looks more like an indentation in the ground.

Is it the Ark? I wouldn’t care to say, though it’s hard to forget it’s certainly not on Ararat – though some of the other evidence presented makes for a moderately convincing case, and the more you stare at it the more you can see what they’re talking about in terms of the shape.

Perhaps most telling, though, was the fact that, after we’d left the Visitor’s Centre and were in the minibus once again, the group was quiet, as if each of us was thinking about our reaction to what we’d just seen, and reaching a conclusion.

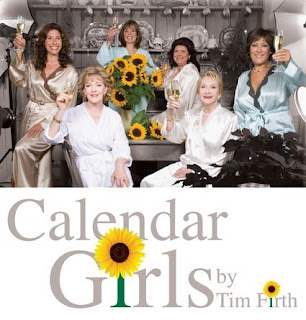

I was slightly wary about going to see this play, as it could have looked as if I was sloping into the theatre in the hope of seeing a burlesque show starring women of my mother’s generation, so I wore my hat strategically dipped below one eye and my scarf covering my face, and nobody seemed to notice anything amiss.

I was slightly wary about going to see this play, as it could have looked as if I was sloping into the theatre in the hope of seeing a burlesque show starring women of my mother’s generation, so I wore my hat strategically dipped below one eye and my scarf covering my face, and nobody seemed to notice anything amiss.