This year, I’m making a concerted effort to read more books by women, and so recently I decided to read some Jane Austen. I read Emma years ago at school, but that was a different kind of reading (and I guess that with it being decades ago, you could say that I was a different kind of reader). Austen’s often cited as a great writer, and arguably her most famous work is Pride and Prejudice, so that was the one I picked.

My emotions, once I’d finished it, were kind of mixed – to follow Austen’s approach to titling, I’d sum them up as being Amusement and Anger.

Let me explain…

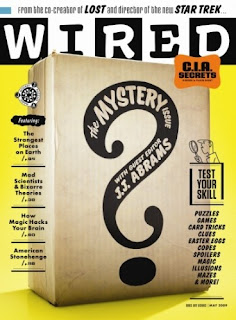

The opening line of P&P (as the groovy cats all call it, so I’ll call it from here on) is famous, and oft-quoted – so much so that I commented on this in a tweet from 2015:

That’s right, I’m quoting myself to back up my point. Bold, I know.

But… well, okay, let’s just quote the line for those of you who may not be familiar with it:

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.”

Pretty bold assertion, really, presented as something which is both true and held to be true (reminds me of that bit in the US Declaration of Independence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident…”), and I’ll be honest with you, it’s never really rang true for me – I understand that Austen’s setting out her whole premise for the book, really, but when ever I’ve seen this line quoted it seems to be saying ‘this is the basis of the story, and everything spins from here, so accept it as true’, and that’s never really sat well with me – not just because the social aspect lurking in it is very old-fashioned to modern eyes, but also because there must have been people even in Austen’s days who didn’t feel that way (must have been some men with a fortune who didn’t want a wife, for whatever reason, surely?).

As I say, I’ve only ever seen this line quoted with no knowing wink or suggestion that it’s a joke, and … well, to my mind, it is a joke (or at least the setup of one), because the next line totally undermines it – here it is:

“However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters”

… so Austen says that ‘everyone knows that a single man with money wants a wife’ and then follows up by saying ‘I mean, if one moves into your town, unmarried daughters basically think he’s their property’. Feels like a joke to me, and – olde worlde language and ideas aside – not a bad one (probably not least because I’d always seen the first line presented as a self-contained statement of fact, not the feed line of a sarcastic joke).

So, that was page one, and I started to wonder if the people who’ve adapted Austen’s books over the years, and who talk about her work, seem to be misrepresenting; the seeds of my amusement and anger, before I was even a page into the book. Hmm.

Because as I read on, amusement was a consistent feature of my experience of P&P, as it is genuinely funny (though as I mentioned above, some of the jokes are kind of buried in the formal language, or poking fun at social conventions which are now very outdated, though in its way that shows how progressive Austen’s thinking was), with the dialogue in particular containing a lot of sharp retorts and … well, the ancestors of the sort of snappy patter that so many onscreen will-they-won’t-they couples have traded ever since.

This TV show lived – and died – by that dynamic

As I say, quite a bit of the humour has a sarcastic edge to it – for instance, there’s a sequence (I read the feedbooks ePub version – this was p54 if you want to read along) where Miss Bingley tries to flirt with Darcy (don’t forget it’s universally acknowledged that he has money and a pulse and therefore is up for grabs) by sitting next to him while he reads, and pretending to read the book that follows from the one he’s reading – though of course she has no idea of what it’s about, not having read the first one, and then she says “There is no enjoyment like reading! How much sooner one tires of anything than of a book!”

Oddly enough, I often see this quote on tote bags and the like, attributing it to Austen herself, which feels a bit off as the character who says it hasn’t even been reading properly, and the line’s designed to show she’s insincere – odd that it’s often quoted straight when it seems to be sarcastic in intent.

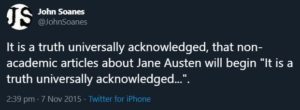

One thing which I really enjoyed was that Austen seems to be very aware that people kind of ‘enjoy their emotions’ – I don’t just mean the tendency which a lot of people show nowadays to be ready to be offended (often on other people’s behalf, which feels a bit hmm), but Austen’s very astute about the fact that people get a bit of a thrill about holding strong opinions on things – obviously there are people on TV and in the newspapers who’ve made a career out of being professionally controversial (my thoughts on that career path, in summary: I question their sincerity), but I’m also reminded of a lot of people online who seem to enjoy being firm about their opinions, at being appalled or impressed by something, and jumping quickly into whichever team that makes them part of, all of which may not leave much room for nuance or uncertainty, which is often much-needed.

Austen seems to have a terrific handle on this, both the phenomenon and the delight people take in being part of it, as she wrote that Elizabeth Bennet wallows in her feelings by taking “a solitary walk, in which she might indulge in all the delight of unpleasant recollections” (ch 14) and later that she “meant to be so uncommonly clever in taking so decided a dislike to him, without any reason” (p215) – that latter remark feels very much like today’s online snarking and trolling, to my mind.

Colin, the energy vampire from What We Do In The Shadows wants to tell you why you know nothing

I mentioned a couple of lines ago about people enjoying being on a team where they’re all holding one opinion, and Austen seems aware of how team spirit can turn into mob mentality, noting that a group of people “indulged their mirth for some time at the expense of their dear friend’s vulgar relations” (ch 8) and that other people could be swayed by this pack mentality when it comes to holding opinions as “their indifference… restored Elizabeth to the enjoyment of all her former dislike” (same chapter). I think Austen’s on to something quite important here – not only the way people behave, and the opinions they hold, but the way it makes them feel when they do so; delighted to have someone to look down on, or just pleased to be able to hold a strong opinion.

Of course, the problem with aligning yourself to a position this way is that if you turn out to be basing it on an incomplete picture, or there’s some dramatic change of events, you need to change your position, but without in any way looking like your judgment might be as flawed as it actually is, and Austen nails this fickleness of opinion, and our ability to rewrite it on p275 when it turns out that one character was a bad ‘un, and we’re told that “Everybody decided that he was the wickedest young man in the world; and everybody began to find that they had always distrusted the appearance of his goodness”. I’m sure we can all think of a number of instances where people have suddenly claimed never to have liked someone or something because there’s new evidence against, even if they seemed a fan previously…

Generic image: impose your own idea of someone whose work you liked but who put you in an awkward position psychologically by turning out to be profoundly unpleasant

The social stuff underlying much of the story looks pretty old-fashioned now, and the plot arc seems to tend inescapably towards characters getting married, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the men are all moustache-twirling predators (though some are close – I’ll get to that in a few lines’ time) and the women utterly subservient and happy to marry someone as long as he’s got a good fortune and a backbone.

The main character, Elizabeth Bennet, is solidly defined, with her own opinions, though this does bring her into conflict with some, as (in ch18) Mr Collins cheerfully says “… I consider myself more fitted by education and habitual study to decide on what is right than a young lady like yourself.”

This would be his Twitter avatar

Whoa. I mean, he’s modern in that he comes over like a man replying to a woman online – and actually, in the story, he proposes marriage to her the next morning, so in a way he’s like some kind of proto-Pick Up Artist, ‘negging’ Elizabeth in the hopes that that her self-esteem will take such a bash she’ll do anything to get him to like her (spoiler: it doesn’t work, she marries Darcy).

Speaking of Darcy, the romance element of the book was almost surprising to me, as I’d been under the impression that the whole thing was like Much Ado About Nothing or When Harry Met Sally or the like, in that I expected Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy to say they didn’t like each other until the final chapter or so, when misunderstanding would be untangled, and they’d declare their love for each other at an annual ball or something like that.

But Austen uses the narrative trick of a generally quite all-knowing narrator, and so we get insights into the characters which kind of short-cut that sort of thing, as in ch10 when she states matter-of-factly “Darcy had never been so bewitched by any woman as he was by [Elizabeth]”. According to my e-version of the book, this is about 13% of the way in, and when it comes to Elizabeth actually being made aware of this, even that isn’t at the end – what would probably be expected to be the big reveal at the end comes about midway through it… reminding me of the terrific revelation in Gone Girl (both the book and the film).

Spoiler: the girl is gone

As an aside, I found it interesting how little of the time Darcy’s actually present on the page – he’s like Holmes in The Hound of The Baskervilles or a plot catalyst like the imprisoned Hannibal Lecter, with other characters reacting to him and speculating about him. Perhaps this is a version of the ‘blank page’ thing, where the other characters and the readers alike, in the absence of concrete details, project their own ideas and expectations onto him?

On a related note to the above, one thing which stood out to me was a general absence of physical details or descriptions of the characters, though Austen often them as being handsome or agreeable-looking without being specific; in a way, this makes their appearances almost future-proof as if she knew that what was attractive in 1813 when P&P was published might well change; a healthy tan from the sun isn’t likely to have been an expected feature at that time, I’d imagine, but now that might be cited as appealing. Similarly, Austen sometimes cites character traits without actually showing them in action, which feels like a classic case of telling, not showing, but generally it works.

Just to break up the format a bit here (and mindful of the long sentences I appear to be unable to avoid using), some bullet-points with stray thoughts about the book:

-

There’s a character called Jane, who we’re frequently told is attractive, and this made me laugh – yes, I know she wasn’t named on the cover of the book at the time of publication, but this is kind of funny and would probably be rare now… though when I think about it, Clive Cussler put himself into loads of his Dirk Pitt novels, and it seems pretty obvious that James Bond was living a life Ian Fleming seemed to want. So perhaps Austen was one of the first women to do this kind of self-fictionalisation?

-

Quite often, I lost the thread of who was being talked about – there are four ‘Miss Bennets’ in the book, and it’s not always clear who’d being discussed, and sometimes pronouns like ‘she’ are used in sections with multiple female characters, so you can end up having to re-read bits to make sure of your understanding. The sort of thing that might be caught by a line edit nowadays, I guess.

-

There’s a very Wildean epigram (pre-dating Wilde’s birth by four decades, so I’m not suggesting plagiarism) on p319: “We all love to instruct, though we can teach only what is not worth knowing”

-

There’s a key turn of events just after midway in the story when Darcy writes Elizabeth Bennet a letter, revealing to her (and the reader) a whole load of stuff which has happened off-page, but which Elizabeth has reached inaccurate conclusions about. In terms of sheer text on the page, the long letter from Darcy is a huge infodump, but then again it’s realistic for a means of communication at the time … there’s a follow-on sequence of Elizabeth working through her emotions and thoughts as a result of the fuller picture she now holds, which in all honesty I found kind of dense and often tangled, and I was wishing by the end of it that this section had been woven in to the narrative of Darcy’s letter (alternating his comments and her reactions), though then again it did shine a light on what we’d now probably now call ‘cognitive dissonance’ on her part (that is, she thought Darcy was more mean-spirited than he actually was).

-

I alluded to the omniscient narrator approach above, and there’s a slightly odd case of this when the reader only sees how ‘vulgar’ Elizabeth’s sisters are in their demeanour after Darcy’s letter comments on this, and Elizabeth re-views events through that lens now (esp in Pt2, Ch16), but this feels like a bit of a need for the reader to also go back and re-frame their perception of those events, as we haven’t actually had this depicted as sharply in the narrative before. I guess it’s not exactly an unreliable narrator here (I refer you to Gone Girl, cited earlier), but we could charitably refer to this as withholding, or what m’colleague has referred to before as a ‘veiled plot’, but then again one might argue it makes it necessary for the reader to the kind of re-writing of ill-informed conclusions that the characters in the books have to do on a number of occasions.

So, the above is (whether it’s clear or not) derived from my Amusement… what of the Anger I referred to? Well (takes breath)…

I’m angry and annoyed because I feel I would have read Austen for fun much earlier in my life if it had been pushed as being funny – because it is funny; it’s got snappy lines and comedic setups and misunderstandings and cutting putdowns and the like, and lurking under it is a very astute angle on the social expectations of the time (in, to be fair, a very limited section of society). But aside from people occasionally talking about Austen as a social commentator or satirist, I’ve never come across any promotional material for an adaptation of Austen which made this the principal selling point.

Instead, the film and TV adaptations are all lavish, with expensive sets and accurate costumes, but nowhere do they seem to play up the comedy angle. It feels like convincing me to see Bridesmaids because they’ve got a beautifully-recreated set of a wedding shop, and forgetting to mention the funny. I used to say (and I’d be surprised if I was the first to do so) that costume dramas on TV were all costume, no drama, and it feels like the sheer comedy of Pride and Prejudice has been lost as people get distracted by the bonnets, balls, carriages and so on.

Take out the gags, show this pulling up outside a Manor House, it’s what Jane would have wanted

As I was reading the book, I was reminded of how Steven Moffatt and Mark Gatiss had said that the reason Sherlock Holmes was update-able material was because at its core, it’s not about gaslit streets and visiting cards on silver platters and all that Victoriana, it’s about the mystery, and the characters, and so on. And just as the film Clueless took Austen’s Emma and updated it and made it clearly a romantic comedy, I can’t help but think that the fact that P&P is a comedy at heart (and it has heart, yes, it’s a romantic comedy) means it should be eminently possible to adapt it for the screen without getting fixated on the production design. Pride in the big budget adaptations, it seems, led me to develop a Prejudice against the source material.

Because if you can do that, I suspect you might find there are people who would be pleasantly surprised to realise it’s actually a comedy. Because – if I haven’t made it clear from the thousands of words I’ve expended right here in this blogpost – I’m one of those people, and I’m sure I’m not the only one who can get over being Annoyed (at having felt at arm’s length due to mis-selling of the material) if you can make me sufficiently Amused once you draw me in.

I’m currently reading Into The Woods by John Yorke, which (as you may know) is about stories and storytelling. Unsurprisingly, it features quite a bit of discussion of structure, which is a subject I’ve been thinking about quite a lot recently, and in the spirit of self-indulgent sharing, it’s the springboard for this blogpost.

I’m currently reading Into The Woods by John Yorke, which (as you may know) is about stories and storytelling. Unsurprisingly, it features quite a bit of discussion of structure, which is a subject I’ve been thinking about quite a lot recently, and in the spirit of self-indulgent sharing, it’s the springboard for this blogpost. Maybe I’m being optimistic, but I think there’s been a bit of a rise of narratives with unusual structure over the past few years – to give a couple of examples,the success of Gone Girl in both written and filmed form was testimony to audiences’ willingness to watch events play out of sequence, and complex structure was a key aspect of Steven Moffatt’s work on Doctor Who (though he doesn’t need time travel as a plot device to enable this kind of thing, as fans of his earlier work Coupling [and I am one of those fans] will be aware). There are often suggestions that audiences are becoming increasingly sophisticated and aware of how narrative works, and I guess that willingness to accept breaking and bending of the A to B shape of a tale may well be a part of that.

Maybe I’m being optimistic, but I think there’s been a bit of a rise of narratives with unusual structure over the past few years – to give a couple of examples,the success of Gone Girl in both written and filmed form was testimony to audiences’ willingness to watch events play out of sequence, and complex structure was a key aspect of Steven Moffatt’s work on Doctor Who (though he doesn’t need time travel as a plot device to enable this kind of thing, as fans of his earlier work Coupling [and I am one of those fans] will be aware). There are often suggestions that audiences are becoming increasingly sophisticated and aware of how narrative works, and I guess that willingness to accept breaking and bending of the A to B shape of a tale may well be a part of that. But whether it’s part of a wider phenomenon or not, I’ve long been a fan of structure; as a reader, once I recognise it, I find it reassuring (and in the case of Cloud Atlas, it took me until the midpoint of the book to realise what the author was doing, but when the penny dropped, it did so in a very satisfying way), and as a writer – you knew I’d get to this eventually – I find it very useful.

But whether it’s part of a wider phenomenon or not, I’ve long been a fan of structure; as a reader, once I recognise it, I find it reassuring (and in the case of Cloud Atlas, it took me until the midpoint of the book to realise what the author was doing, but when the penny dropped, it did so in a very satisfying way), and as a writer – you knew I’d get to this eventually – I find it very useful. And from a writing standpoint – and especially working, as I do, in the crime/thriller genre where plot is key – there’s something very useful about having a structure to work to; that might be a simple three or even five act structure, it might simply mean having the story starting and ending at the same place or in a similar way to hint at some idea of symmetry, or whatever, but if you have a structure sorted out ahead of time that lets you know what you should be writing about next, then that’s very useful indeed.

And from a writing standpoint – and especially working, as I do, in the crime/thriller genre where plot is key – there’s something very useful about having a structure to work to; that might be a simple three or even five act structure, it might simply mean having the story starting and ending at the same place or in a similar way to hint at some idea of symmetry, or whatever, but if you have a structure sorted out ahead of time that lets you know what you should be writing about next, then that’s very useful indeed. However, given that the story is in itself a ‘ticking clock’ tale with a set ending looming on the horizon and moving closer in stages (akin to most films featuring weddings, for example: the wedding is a fixed point in time and everything we see is drawing us closer to that), it did occur to me that having a race against time which is also viewed through the fragmented narrative of rotating POVs would perhaps be too much to put on top – and given that (again, non-spoiler, given the genre expectations) the paths of the Detective and the Kidnappers will inevitably cross, whose narrative section should I include that in? The Detective closing in, or the Villains realising that things aren’t panning out as planned? I wasn’t sure.

However, given that the story is in itself a ‘ticking clock’ tale with a set ending looming on the horizon and moving closer in stages (akin to most films featuring weddings, for example: the wedding is a fixed point in time and everything we see is drawing us closer to that), it did occur to me that having a race against time which is also viewed through the fragmented narrative of rotating POVs would perhaps be too much to put on top – and given that (again, non-spoiler, given the genre expectations) the paths of the Detective and the Kidnappers will inevitably cross, whose narrative section should I include that in? The Detective closing in, or the Villains realising that things aren’t panning out as planned? I wasn’t sure.