Some people might have felt that my comment in yesterday’s post that “a filmed version of Watchmen makes about as much sense as a musical version of the Mona Lisa” was a bit dismissive and reductionist, so I thought I’d expand on my point – unpack it, if you will.

Watchmen, for those of you who aren’t familiar with it, was a 12-issue comic series released in 1986-7 by DC Comics, the US-based firm who publish Batman and Superman, and who are a small subdivision within Warner Brothers, or Time Warner as I think it’s now known. The series (which was always set at 12 issues, having a self-contained story to tell) was written by Alan Moore and drawn and lettered by Dave Gibbons, with colouring by John Higgins. It was published in monthly(ish) issues, with no adverts, and generally featuring 28 pages of comic story, and 4 pages of background material.

I was going to try to summarise the plot here, but it’s so clever and dense I risk under-selling it by trying to precis down to one paragraph; but it’s definitely one of the first – and most successful – comics to cover the question of what it would be like if there were superheroes in the real world. The writing is more intelligent than the vast majority of comics (and indeed novels), and the art is perfectly judged in all regards – Watchmen is often said to be the Citizen Kane of comics, and whilst that’s true in that it casts a shadow over everything that follows it and remains a standard which few have attained since, the meshing of the creative team feels more like Lennon and McCartney in that they’re both at the top of their game and productively nudging each other to do the best work possible.

As you’ve probably gathered by now, I’m a huge fan, and I’m not alone in that – it won a Hugo Award, and was included in Time Magazine’s 2005 list of the 100 Best English-Language Novels ever. There was steady and solid praise for the comic as it was released in its individual issues, and there was a minimal period of time after its completion before it was gathered into a single volume of 360-odd pages. The collection has remained in print pretty much ever since then, and is a consistently good seller.

Now, after many years of a film version being suggested and multiple drafts of screenplay adaptations having been written, the trailer for the film version to be directed by Zack ‘300’ Snyder has been released (you can see it here ), and there’s been a surge of interest in the original work, coupled with discussion of whether or not it’s a good idea to make it into a film. The creators themselves disagree about this, in fact – Alan Moore thinks it’s a bad idea, but Dave Gibbons has been quite supportive (visiting the set etc), and the two of them have been quite gentlemanly about this (Moore’s made sure his name’s not on it, and has given his share of the money to Gibbons).

My casual point yesterday, though, sums up why I think it’s a poor idea – one of the many charms of Watchmen is the fact that it’s so very specifically designed to do things in the comic medium which you simply can’t do in other medium (obvious example: Chapter 5, ‘Fearful Symmetry’ is arranged so that the scenes and panel layouts on the page are symmetrical – the first page is the same as the last, the second as the penultimate, and so on until they meet in the middle). This sort of detail is something which you can’t transfer to film, and there are many other comic-only narrative tricks and little background elements which won’t make the transition.

Terry Gilliam, who was lined up to direct the film version in the late 1980s, has said that “the problem with Watchmen is that it requires about five hours to tell the story properly, and by reducing it to a two or two-and-a-half hour film, it seemed to me to take away the essence of what Watchmen is about.” Well said, Terry – whilst there are some works which I think can be reduced and compressed in the transition to the screen without any genuine deterioration (‘American Psycho’ and the ‘Lord Of The Rings’ spring immediately to mind), for any work longer than a couple of hundred pages, you’re looking at a question of what to remove. And with something like Watchmen, which is so cohesive and tightly-packed, removal will inevitably equate to loss.

So I think that the creative reasons for the film are pretty feeble, though I’m painfully aware of the commercial reasons – the comic isn’t owned by the creators (I understand that the rights will revert to Moore and Gibbons if the book ever goes out of print for more than two years, which is unlikely since they did such a fine job), and so the surge of interest in the run-up to the film and after its release will mean DC / Time Warner make money from the increased sales of the book and associated merchandise (including some items which are simultaneously ridiculous and creepy ).

On another level, though, the excitement with which comic fans have greeted the film’s trailer strikes me as a bit odd; it’s often as if having a film made of a comic is in some way a validation of the story in question, or even the comics medium as a whole, as if the commercial plan to build on an existing property (unlike adaptations of novels for the screen, comics come with inbuilt storyboards and costume designs) is in some way the same as comics readers being told “hey, you know, your comics are almost like a real artform… they just need to be made into films”.

Okay, I’m overplaying it, but this apparent underdog mentality amongst comic readers (and creators, and publishers, and so on) strikes me as ultimately unhelpful; it’s less prevalent in Japan or Europe, to take obvious examples, but it still seems that UK and US comic readers all too often seem to see a film being made of their favourite comic as the ultimate seal of approval.

There’s really no need for this, surely – Picasso drew a comic strip, comic-related books have won the Pulitzer Prize not once but twice, Alex ‘The Beach’ Garland has written a Batman story … I mean, just how many validations or commendations does the medium need ?

Worst of all, if the Watchmen film loses all the subtlety and nuance of the original work, it’ll be the only experience people have of it, and – as was the case with the frankly useless Judge Dredd film in the 1990s – it’ll mean a lot of people say “Watchmen? Oh, I saw that, it wasn’t much cop” and don’t bother to look at the source material, which would be a shame, as Watchmen is one of those works which everyone goes on and on and ON about, saying how great it is, and when you actually take a look at it, you know what? It’s even better than that.

(Mind you, most alarming is that the Watchmen trailer has been well-received despite featuring music from Batman and Robin, itself a film which hardly helped comics be seen as a serious medium.)

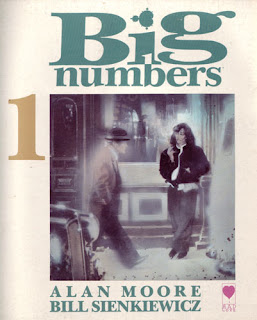

The best part of two decades ago, the comic Big Numbers was launched. As you can see from the cover here, it was co-created by Alan Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz.

The best part of two decades ago, the comic Big Numbers was launched. As you can see from the cover here, it was co-created by Alan Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz.